Analogies: Cultivating a “Thick” Strategy for Thinking Christianly about Communication (Part 2)

Analogies: Cultivating a “Thick” Strategy for Thinking Christianly about Communication (Part 2)

Naaman Wood, Ph.D., Redeemer University College (nwood@redeemer.ca)

In my previous post, I named two potential dangers that come from the typical way many of us engage in faith-learning integration: thin readings and unethical readings. In the next few blog posts, I want to offer a bit of detail on what analogies look like in practice and how they might mitigate these potential dangers. For this post, I want to explore James H. Cone’s The Cross and the Lynching Tree as an example of analogous thinking in action. It is integrative thinking that I count as both thick and ethical. In order to set up the analogy, I offer a bit of historical background on crucifixions and lynchings.

By way of reminder, I count an analogy as a way of seeing or a mode of interpretation that identifies profound similarities between two or more things, events, texts, images, or concepts that are, on the surface, quite different from one another.

Crucifixion in the ancient world

As historian of religion, Martin Hengel, reminds us, crucifixion was a particularly public and political act in the ancient world.[1] It was a form of execution reserved for lower class peoples, particularly rebels against the Roman Empire and disobedient slaves. In addition to the gruesome and harrowing violence, prisoners were often humiliated and shamed in the process. It was not just the reality that those crucified were hung stripped of their clothes, but, as violence against Jesus suggests, torture served to denigrate and humiliate the victim’s claims and actions. The crown of thorns demonstrates to anyone who gazed upon Jesus that, against the power of Caesar, he is no real king. He is merely a failed rebel. Furthermore, the public display of the crucified served a distinctly political purpose. Crucifixion is what happened to those who aimed to disrupt the pax romana. In short, crucifixion constituted a pageant of horrors aimed to preserve the status quo and to keep marginalized people like Jesus in their place.

Lynching in the modern world

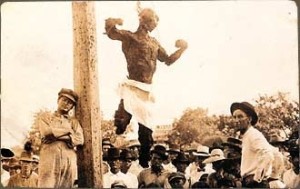

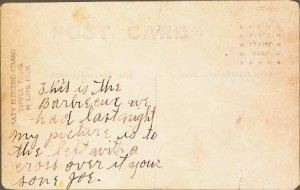

During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, there were thousands of lynchings across the United States. A lynching was an extra or paralegal means of “justice” that whites performed against blacks.[2] While not officially sanctioned by governments, evidence suggests that local, state, and federal governments knew about lynching but did nothing to stop them. An African American could be lynched for almost any reason imaginable: being homeless, stealing, looking at a white person the wrong way, being out after dark. Though the reasons for lynching could be frivolous, the acts of violence were anything but. Lynchers tortured victims in unspeakable ways. Lynchees were hanged, mutilated, and often set on fire. These events were also public and publicized. White folks advertised lynchings in newspaper and on the radio, and they treated such events as social gatherings. It was not unusual for parents to bring their children to lynchings. In addition, lynchings served as entertainment. In fact, a cottage industry for lynching postcards emerged in the late 1800s. Attendees posed with lynched bodies and could purchase the developed photograph printed on a postcard stock. Lynchers could keep the postcard as a keepsake or send it through the mail as correspondence.

It is not an overstatement to say that lynchings produced a fear that haunted African American consciousness; however, these general descriptions fail to represent the terror of specific lynchings, for example the lynching of Sam Hose.[3] Hose was accused of killing his white employer and then raping the employer’s wife. Although Hose did kill his employer, he did so only after the employer had threatened him. Historical evidence suggests that the rape accusation was a complete fabrication. The lynching was planned for April 23, 1899, a Sunday morning right after church in a small town called Palmetto, Georgia, 25 miles north of Atlanta. Once news of the lynching reached Atlanta, an estimated 5,000 white individuals, both adults and children, travelled to Palmetto. The crowd removed Hose from police custody, tied him to a pine tree, and tortured him. A journalist recounts:

[A] hand grasping a knife shot out and one of the negro’s ears dropped into a hand ready to receive it. Hose pleaded pitifully for mercy and begged his tormentors to let him die… The second ear went the way of the other. Hardly had he been deprived of his organs of hearing than his fingers, one by one, were taken from his hands and passed among the members of the yelling and now thoroughly maddened crowd.[4]The account states that the torture of Hose lasted for another half hour as the mob burned him alive over an open fire. When Hose expired, “the crowd cut his heart and liver from his body, sharing the pieces among themselves, selling fragments of bone and tissue to those unable to attend. No one wore a disguise, no one was punished.”[5]

Charred corpse of Jesse Washington suspended from utility pole. May 16, 1916, Robinson, TX. Gelatin silver print. Photo postcard. 5½ x 3½”[6]

Back of postcard. The author writes, “This is the barbecue we had last night. My picture is to the left with a cross over it. Your son, Joe.”[7]

A historical analogy

It is important to note that Christians have been unwilling or unable to see any similarity between crucifixions and lynchings. It appears as true of black Christians as it is of white Christians, although for vastly different reasons. While Cone regularly attended church, he can recall no mention of lynching, much less thinking it similar to Jesus’ cross. This absence might be considered conspicuous, because the black church made emphatic connections between Jesus’ suffering and black suffering. Just as God was present in Jesus’ suffering and death, African American Christians sang and preached that God was present with them in the terrors of their own experience. Jesus’ cross, therefore, served as a sign of great hope in the midst of slavery, Jim Crow segregation, and the tide of white supremacy that never seemed to ebb. Nevertheless, lynchings remained that unspeakable event within the black community. It seems to be a space too dark for even the hope of Christ to penetrate.

Likewise, white Christians showed and continue to show very little interest in the reality of lynching. Cone draws specific attention to Reinhold Neibuhr, one of the black theologian’s primary influences. Despite the fact that Neibuhr used the cross to address a host of injustices in American life, he showed no interest in lynching. Because Christians seem unwilling or incapable of turning their gaze toward the atrocities of lynching, this lack of attention suggests that most Christians do not see any deep connection or similarity between the cross and the lynching tree. Historically, Christians tend to assume only difference between these forms execution.

Against the widespread assumption of dissimilarity, Cone learns from black artists and poets what should have been patently obvious: the cross and the lynching tree share a great deal in common. Like crucifixions, lynchings were pageants of horror that aimed to forge political realities. Lynchings served to keep the political status quo of white supremacy in place. The violence, shame, and humiliation of lynchings sent a clear message to blacks—this is what happens to those who might upset the order of things, the order of white control over black bodies and lives. Both events involved torture. Both events involved lifting the victim on high. Both events were public. Victims were seen as criminals. Perpetrators were seen as good citizens. Both events struck fear into lower classes.

Cone encourages us to see the events as historical analogies, as events that have a deep resonance or transparency to one another—the cross was a lynching and lynchings were crucifixions. To think of the cross as a lynching is to regain for many Christians a deep sense of, what theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer calls, costly grace. Like those black Americans who suffered in vile and unspeakable ways, so Jesus’ was experience vile and unspeakable.[8] To think of the cross as a lynching is also to remember that, as the Gospel of Matthew reminds us, God identifies and experiences solidarity with those who suffer. In reference to the hungry, the prisoner, the naked, the sick, Jesus says, “whatever you did to the least of these…you did it to me” (Matthew 25:40). To think of the cross as a lynching is to think of lynchees as our American version of the “least of these.” To think of the cross as a lynching is to admit that whatever Christian Americans did to lynchees, they did to Jesus.

To also think of lynchings as crucifixions opens up the deep possibility that the death and destruction of these events do not have the final say any more than the cross did. For many black Christians, the lynching tree was that unspeakable event, that event of absolute dereliction, that place where the hope of Christ could not be found. For Cone, “the lynching tree also needs the cross, without which it becomes simply an abomination.”[9] To think of lynchings as crucifixions is not to deaden the horror of those horrors on American soil. Rather, it is to hope beyond hope that there is life after death. Cone reflects, “The cross helped me to deal with the brutal legacy of the lynching tree, and the lynching tree helped me to understand the tragic meaning of the cross.”[10]

Thick? Ethical?

I think Cone’s analogy constitutes a dramatic improvement over one-to-one comparisons, precisely because the analogy offers a thick reading with ethical concerns at its core.

I count Cone’s work as thicker for two reasons. First, the analogy opens up space to press into the historical particularity of these events and, therefore, extend what we think we know about our faith and the world in which we live. After encountering Cone’s work, I am constantly forced to rethink what I think redemption is. Redemption has a deep sense of loss, tragedy, abjection, and fear built into its architecture. Were it not for Cone’s analogy, I might be tempted to think of Jesus’ crucifixion as bad but not that bad. Rather, whatever God offers us through redemption must come through horror, and I see that divine horror more clearly when I, like Cone, have the bravery to turn my gaze toward those who are crucified in our midst, toward, in this case, lynched black bodies. Second, Cone points to similarities between the cross and the lynching tree against the widespread assumption among white and black Christians that the events are fundamentally different. Like all good metaphors, it is the tension between similarity and difference that gives them their power. Cone’s insights draw on a similar tension, and that tension provides at least some of the charge and edge to his work.

In contrast, part of the thinness of redemptive readings of Gran Torino is that they fail, for me, on both counts. I cannot say that they teach me very much about what it is I think I know about my faith or the world around me. And it works with very little by way of difference. It is rooted primarily in similarities or against the widespread assumption that a “crusty-but-benign” old white man can be a Christ figure.[11] It is a significant difficulty to imagine a charred and disfigured black body dangling from a tree to constitute anything close to a Jesus icon.

Similarly, the cross and the lynching tree centralize ethical considerations. In bringing these two events together, Cone presses into urgent social and theological issues of race, American history, violence, and Christian identity. After Cone, it is difficult for me to think of lynchings as some event locked away in America’s past. The legacy of lynching casts a long shadow over both black and white Christianity. Cone has convinced me that to ignore that shadow is to stand idly by while black bodies burn. To do so denies the very presence of Christ in the midst of those who suffer. It is, to quote Hebrews 6:6, to crucify “again the Son of God” and hold “him in contempt.” In the face of such injustice and suffering, Cone wonders what Jesus has to do with lynching. As it turns out, he has everything to do with it, because, as the black church has always known, the cross brings God into the center of black suffering. His willingness to press into these sufferings stands in stark contrast to redemptive readings of Gran Torino. As Annalee Ward reminds me, those readings tend to prove blind to injustice. Cone’s analogy makes it a bit more difficult for me to sustain that blindness.

In my next post, I will respond to a question one reader posed on some specifics concerns about how I define and use analogy.

NOTES

[1] Martin Hengel, Crucifixion: In the Ancient World and the Folly of the Message of the Cross (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1977), 86-88.

[2] James H. Cone, The Cross and the Lynching Tree (Maryknoll NY: Orbis Books, 2011), 3.

[3] Special thanks to Kevin Miller whose research on Sam Hose’s lynching I use here.

[4] “Negro Dies,” The New York Times, 1899.

[5] As cited by Edward L. Ayers in “An American Nightmare,” review of Trouble in the Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow, by Leon F. Litwack, The New York Times (May 3, 1998), paragraph 2.

[6] James Allen and John Littlefield, Without Sanctuary: Photographs and Postcasts of Lynching in America, accessed April 8, 2016, http://withoutsanctuary.org/main.html.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Cone, The Cross , xiv.

[9] Ibid., 161.

[10] Ibid., xviii.

[11] Paddy Chayefsky, Network, directed by Sidney Lumet (1976; Warner Home Video, 2006), DVD.