Teaching Communication and Theology

Teaching Communication and Theology

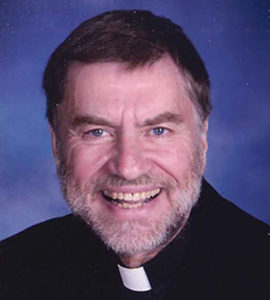

Paul A. Soukup, S.J.

Professor of Communication

Santa Clara University

psoukup@scu.edu

Originally presented to the Arricia Conference on Communication and Theology, Arricia, Italy, 2007

Journal of Christian Teaching Practice Home Page

Abstract

A media ecology approach allows a better integration between theology and communication, either as a unit in an existing course or as a stand-alone course. Teachers can further borrow an approach from catechetical instruction and highlight the communicative aspects of theology by presenting the Christian collection, cult, creed, community, and code as broad areas of study. The presentation shows how each of these depends on communication and how teachers can use the media ecology approach to introduce students to relevant literature and habits of thought.

KEYWORDS: communication, theology, media ecology, orality and literacy, religious expression.

Introduction

Most approaches to integrating communication within the theological curriculum situate communication as a more or less welcome visitor. Those who regard communication instrumentally make it more welcome–after all, homiletics and other modes of proclamation and evangelization rely on communication; one can find warrants extending historically back to the time of Augustine, writing in the De Doctrina Christiana (1947). Other, still welcoming, find in communication a tool for better understanding a given culture, what John Paul II in his encyclical Redemptoris Missio (1990) identified as the Areopagus of the media. Both take a kind of media education approach: teaching the basics of communication better prepares the pastoral minister for proclamation and teaching within a contemporary culture.

Other approaches do not find communication such a congenial guest. Some recognize its contribution but feel that other topics merit more curricular time. Some feel an acknowledgment suffices, as seminarians need no special training or preparation in communication. They just need something to say; teach theology, this thinking goes, and the rest will take care of itself.

Here, I propose a more integrated approach wherein communication and theology appear as related disciplines, not only on the instrumental level but also on the conceptual and cultural levels. In this essay I will both describe a method of teaching and provide some examples of the application of that method. The approach takes its intellectual lead from media ecology, an approach to communication study that regards communication not so much as a tool or as a cultural force, but as an environment (Strate, L., 2004). Strate credits Postman with the naming of this approach:

Postman did, however, provide a definition of media ecology as “the study of media as environments” (Postman, N., 1970: 161), explaining that the main concern is “how media of communication affect human perception, understanding, feeling, and value; and how our interaction with media facilitates or impedes our chances of survival. The word ecology implies the study of environments: their structure, content, and impact on people” (p. 161). These environments consist of techniques as well as technologies, symbols as well as tools, information systems as well as machines. They are made up of modes of communication as well as what is commonly thought of as media (although the term “media” is used to encompass all of these things). Thus, Postman also describes media ecology as “the study of transactions among people, their messages, and their message systems” in The Soft Revolution (1971: 139), which he co-authored with Charles Weingartner. (Strate, L., 2004: 4)

Media ecology encompasses human communication and, with its emphasis on modes of thought as well as symbols, suits theological investigation quite well. Theology, too, forms an environment for people, although only a part of the larger environment we call religion or religious practices. As a kind of advanced analysis of religious symbols and meaning (as well as the construction of religious meaning), theology creates an environment for belief.

Attending to the communication environment of religion and to the religious environments in which we live allows us to move more smoothly between communication and theology. To facilitate this in a course (or curriculum), we can borrow Harris’s (1989) structure for teaching from catechetics, as adapted by Lytle (2005). According to Lytle, contemporary religious or theological education can find a structure in Harris’s reading of the key educational moments in the Acts of the Apostles: koinonia, didache, leiturgia, kerygma, and diakonia. With an eye to communication technologies, Lytle translates these as community, creed, cult, collection, and code (Lytle, J., 2005: 64-66), but her terms also serve to identify the overlapping environments within Christianity and, in fact, can each describe both a theological environment and a communication environment.

Koinonia or community refers, obviously, to the basic gathering of the disciples, the followers of the risen Christ. And so, in itself, it describes the fundamental environment for theology: an environment of faith, love, conversation, mutual encouragement, teaching—the basic identity of the Church. At the same time, a community is an experience of communication; no community exists without communication, since, as so many sociologists and communication scholars have pointed out, communication creates and re-creates communities, generation after generation (Mead, G. H., 1962; Duncan, H. D., 1962; Giddens, A., 1984).

Didache or creed describes the basic teaching or formalized belief of the Church. It constitutes that body of expression, sometimes formally defined, that distinguishes a member of the community from a non-member, what Brown and Duguid (1995), following Anderson (1991), call a boundary object. This, too, results from communication and often, as we shall see, involves communication technology, particularly writing, to make the materials more permanent. As such, these boundary objects guide subsequent communication.

Leiturgia, liturgy or cult, refers to the public performance of belief—the worship of the community, as well as the communication that supports that worship. Because of the nature of worship, we see here extensive use of communication forms and indeed discover the greatest creative expressions of the Church in this area. Liturgy brings art, architecture, music, poetry, and the decorative arts—the whole panoply of communicative forms—into consideration.

Kerygma, what Lytle terms collection, describes the proclamation of the good news of the Risen Lord. Theologians and biblical scholar employ it as a specialized term for the preaching of the early Church and for the later core of evangelization. It, too, has a clear communication dimension. Lytle expands the theological core meaning to “collection” in order to include the varied content of the kerygma: the oral tradition of stories about and from the Lord, the collective preaching of the apostles, the recorded proclamation in the Scriptures, and so on.

Diakonia refers to service or to Christian life. Here, Lytle departs from the tradition and calls this “code,” in an attempt to highlight the behavioral elements of Christian life. Her emphasis carries us into the realm of ethics or moral theology. These, too, have clear connections to communication, either as a moral guide for communication action or as dependent upon communication as a foundational moral principle governing Christian life.

If we would use this framework to develop an integrated relationship between communication and theology (from the perspective of media ecology), then we need to re-order their presentation, moving away from an initial theological framework to a more developmentally-oriented one. I suggest this order: collection, cult, creed, community, and code. We begin with the stories of Jesus, the oral tradition at the heart of Christianity, then turn to Christian worship, and then to the development of creedal statements. This order corresponds with the growth of the early Church. Next we consider community and finally, moral codes. Each of the five general categories allows us to examine an interaction of theology and communication in which we see how each forms an environment for the other. Given my own background in communication study, I shall stress more the communication aspects in this essay.

Collection

Harris and Lytle use the term “collection” to refer to the body of religious stories or texts that define the Christian tradition. This primarily refers to the Old and New Testaments (or the Hebrew and Christian Bibles); however, it can also refer to the stories (religious or non-religious) that people use to discuss their own belief. John Shea (1980) argues that these “stories of faith” constitute the primary way that people come to know about God or expect to meet God in their lives. All of the expressions of faith, both personal and Biblical, make up the collection at the heart of Christianity. This approach examines specifically religious communication: the Bible, its communicative form, and how communication affects it. It also takes students to more contemporary methods of storytelling, particularly in film and television.

Storytelling comes from the most ancient of human communication practices. Even in prehistoric times, people told stories, not only for entertainment but to preserve knowledge of the important things in their tribes and groups. In fact, in cultures without writing, the only way to pass knowledge from one generation to another, or even from person or group to another, was through some easily remembered narrative. Without a technology for preserving knowledge, there was no knowledge (Ong, W. J., 1982). Typically, contemporary cultures depend on the various technologies like writing to preserve knowledge; collectively, these form “literate” cultures. A culture without writing, an oral culture, can only know what it can remember. That also means that a great deal of the collective energy of every oral culture is focused on memory: remembering how to do important things (hunt, make tools, grow food), remembering who they are (stories of ancestors, Gods, creation, the land or sea), and remembering how to act (codes of behavior), and so on.

Oral cultures are not without technologies, though. Over the centuries human cultures developed all kinds of memory aids, so that the cultures could remember things. As Walter Ong points out in Orality and Literacy (1982), these aids shape not only the ways that people remembered but also the ways that people thought. What better way to help memory than to think memorable thoughts? These “memorable thoughts” acted as pre-built packages. We’re still familiar with some of them today, since all of us began life without the technology of writing (though we learn it early on). For example, oral cultures make use of all parts of the body to help them remember: singing, dancing, acting out rituals, moving in certain ways, keeping rhythms. Oral cultures use every aspect of language: rhymes, metrical patterns, and repetition through synonyms. Oral cultures put things into narrative forms, as stories with their plots are easier to remember than are abstract formulations. Oral cultures draw on the whole community to help remember; they tell, they repeat the same stories over and again. Ong refers to this as the “noetic economy” of the culture. “Noetic” means “having to do with thought,” so that economy is the set of ways in which the culture governs and regulates thought. Religion (and its more consciously constructed form, theology) is itself also a noetic economy.

One group of the most important stories for oral cultures is the religious story. While students might examine the religious stories of any culture (and all cultures have religious stories), a theology course usually limits its exploration to the Judeo-Christian tradition. The earliest stories about belief come from the Old Testament (or Hebrew Bible), but oral forms persist well into the New Testament period. Dunn (2001) provides a wonderful biblical commentary on the orality of the New Testament, an approach which introduces students not only to Scripture studies but also to the importance of communicative form for the construction of the canon of the Scriptures.

For those who investigate this approach to theology, the focus is on both the form of the story and the content. Ong argues that the form limits the content: if you are going to tell a story, then the story can only have a certain number of characters; it must have action; it must have a limited time span; and so on. A number of others (Tilley, T., & Zukowski, A. A.., 2001; Boomershine, T., 2001) ask what happens if we take stories or narratives seriously as a way of understanding how we experience God, as a way of thinking about God. They further argue that narrative forms more powerfully express theological thought today, particularly in the electronic media. From here, a communication and theology course has several options. First, teachers can direct students to tell their own stories of faith or to collect stories of faith from others—wonderful opportunities for them to engage each other about faith. This kind of storytelling brings them into a theological habit of mind, one that prepares them for homiletics and teaching.

Second, teachers can direct the students to the prevalence of stories in contemporary culture. In doing so, they invite students to explore this communicative form of theology—perhaps one that they know intuitively or find most congenial—that dominates contemporary culture. Storytelling comes naturally to them; a conscious and critical study opens up the possibility of examining the contemporary process of storytelling, especially in film and television. A more anthropological or ethnographic look at religion today finds that many young people, for example, create religious meaning based on the narrative worlds they find in popular culture (Clark, L. S., 2003). Such cultural formations manifest a kind of religious bricolage (Lévi-Strauss, C., 1966), gathering interesting or even bizarre elements from many religious traditions to picture a world of good and evil, a world that gradually brings order from chaos, a world that provides a sense of security and predictability. Clark notes how many young people embrace a detailed angelology or demonology, based on popular teen shows. The religious impulse remains strong, but the narratives that many discover are only partially Christian narratives.

This kind of examination of both the religious and the media ecology gives students of theology a set of tools to better understand the culture in which they will work. Rather than beginning with a systematic theology, they begin with a process in which theological meaning emerges. Students benefit from this approach in two ways. First, they encounter the process in both the Scriptures and the media world. Second, they can themselves gather stories of faith, to better understand the narrative impulse in themselves and their contemporaries. Working with stories helps them to develop their own communicative theology and can form the basis for subsequent reflection.

Cult

Harris’s and Lytle’s second category, “cult,” refers to how the Church worships. Here, too, communication plays a role. Worship combines nonverbal and verbal communication in a complex expression of faith. Worship includes ritual—scripted, repeated actions that allow us to focus our attention on God rather than on what we are doing. Rituals allow us to enter into a different kind of consciousness. Most of the time, this takes place in group settings; hence, one role of communication.

The late communication and journalism scholar, James Carey (1989), argues that communication itself should be described as a ritual. Most of the time, he writes, students regard communication as a kind of delivery system—getting a message from a sender to a receiver. However, communication is really about connecting people, about the things we do on a regular basis to build up those connections. When we say, “Good morning,” to someone, the fact that we are saying it and saying it every day matters more than what we are actually saying. The ritual matters more than the content. The ecological perspective asks students to bring this kind of reflection to bear on the interaction of communication and theology as each acts to create the experience of ritual or worship.

Such emphasis on process over content may occur in Christian worship, but there are other components. The context of the rituals is meant to teach people about the “collection,” the story of Jesus. The narratives become part of the worship. In fact, the most common Catholic ritual, the Mass, not only retells the story of Jesus, but acts it out in an extraordinarily complex ritual that draws on all our senses.

In such an approach to communication and theology, students can learn a lot by examining what each aspect of Christian worship communicates, particularly about God and their relationship with God. There is a theology—a way of thinking about God and the conclusions people draw about God—contained in how they worship. Catholic worship stresses the physical and its importance: this is a theological affirmation that the flesh is important. (This, of course, demonstrates the logion, lex orandi, lex credendi: here we see how the practices of worship manifest the content of belief, in this instance, the Incarnation.) This Catholic and Christian insistence runs completely counter to those religions that deny the value of the body or try to escape into a purely spiritual world. This emphasis on the importance of the physical world also underlies the Christian emphasis on service and love of neighbor.

In studying cult, or Christian worship, students examine a number of communication aspects—image, architecture, space, movement, smell, music, poetry, and story. In addition, students again turn to popular culture and explore the ways in which contemporary artists make theological statements through music, film, and television in a kind of extension of worship outside the church buildings. In this way, a realization about collection is brought into the consciousness of practice.

Cult also offers several points of entry for reflecting on communication from the history of Christianity. For example, images posed a problem for the Christian church. The Hebrew Bible or Old Testament forbade the making of “graven images” as a way to curtail the worship of idols. But the Greek and Roman cultures that the early Christians lived in made use of images. By the third century, we find evidence of Christian images, both decorating tombs and appearing in places of worship. Eventually the Second Council of Nicea in 787 decided that images were consistent with Christian belief. This decision flowed from theoretical and practical reasons: theoretically, images shared in that valuing of creation, of the physical shown in the Incarnation (if the human form was good enough for God, the thinking went, then it was good enough to decorate churches); practically, images helped those who could not read to know the Christian narratives by showing them in pictures or statues (Goethals, G., 1990, 1999). Here, the church joined images to its narrative or collection. In fact, church buildings themselves took on a teaching role by incorporating statuary and images within their spaces (Ferree, B., 1898).

Space itself plays a role in all of this. The whole notion of a “sacred space” or “sacred place” is gradually transformed in later Judaism and then in Christianity (Soukup, P. A., 2003). As we trace what happens in worship, we trace, too, a shifting theological conclusion about how we experience God and what our relationship with God should be. Architecture continues the theme. The ways in which worship spaces were built also makes a powerful nonverbal statement. Who stands or sits or kneels where? Does the space lift up our hearts and minds? What about the use of light? (Goethals, G., 1990: Ch. 1-2). These historical considerations offer another way to encourage students to think theologically: why did communicative form cause such diverse reactions within Christianity? What do these patterns of communication reveal about key theological values and concepts?

It may also help students to contrast different Christian understandings and practices of worship. The Catholic Mass stresses ritual and action and images while Protestant worship stresses the biblical word and the sermon more. Obviously this varies with different Protestant groups. But the variation and the contrast express very important theological differences among the different denominations—the different communication behaviors and practices signify different theological principles. Here again, the media ecology reflects a theological one; communication offers a good vantage point from which to discover theology.

Taking the perspective of cult and including the wider media world allows the examination of secular settings as well as religious ones. There are other forms of religious expression in worship beyond art and place. Invite the students to think about music, but expand this beyond just Church hymns to any kind of music. What about Gospel music? Christian rock? Is there any difference in the music between these and other kinds? Classes could do the same kind of exercise with film or television. Can film serve religious expression? Such a consideration opens the door to a vast literature on film that raises important theological questions (see Lindvall, T., 2004, 2005 for detailed overviews, but also Blake, R. A.,, 2000, Lindvall, T., 2007, Soukup, P. A.., 2002, and May, J. R., 1997 for other approaches).

From the perspective of communication, both music and visual media can have religious significance. Without going into great detail here, we can simply note that both have strong ritual aspects and both serve to focus our attention in ways unlike oral or written communication. In some ways, too, both music and cinema have ties to worship. We have seen how visual images play a role in Christianity; those who study the religious aspects of film begin there, with images and the human experience of images (Martin, T. M., 1991). Music, too, plays a role in Christian worship, with a long tradition of hymnody from the medieval period’s Latin chants to the various Mass settings of classical music to contemporary hymns, Gospel music, and Christian rock. These forms open out onto the realm of popular culture and the dividing line between religion and culture established by secularism. Individual classes or entire courses could explore the nature of liturgy and worship from the perspective of these communication media.

Theological students should consider entertainment and its impact on theological reflection. Clearly entertainment—drama, music, art, and so on—has existed from the beginnings of culture and has often served religious purposes. The Renaissance saw the increase of non-religious themes; some would argue that art and entertainment itself starts to function as a kind of parallel religious discourse (Goethals, G., 1981). As the Reformation pushed visual images and many kinds of music out of the Protestant churches, these grew separately in the secular realm. Rapidly moving to our own day, we experience a popular culture that takes on many once religious forms; we also experience a popular culture that takes on the religious tasks of explaining the world, answering ultimate questions, and so on.

Blake (2000), writing on Catholic film directors, argues for a religious aspect to the cinema based not only on film themes but also on the approaches that directors take. Certain kinds of storytelling seem more religious than others. Blake identifies several characteristics of a “Catholic imagination” (sacramentality, mediation, communion, saints, the physical, etc., Blake, R. A.., 2000: 13-16) and shows how these appear in the films of directors who grew up in the Catholic tradition. One could probably do the same with a Protestant imagination as well. Others, like Schrader (1972), have argued for a “religious aesthetic,” a way of creating or framing a visual image, a way of editing scenes that moves the viewer to an experience of transcendence. The impact of the film does not come from the plot, story, or special effects, but from the way of seeing. Fewer people have applied this approach to popular music, but it seems intuitively possible. Many agree that music can have a religious or transcendent quality; sometimes this occurs with instrumental pieces and sometimes with vocal pieces. Some writers focus on song lyrics.

The larger discussion moves this out into popular or secular culture. Religious impulses do not disappear. I would argue that there is a “popular” theology embedded in the culture in which we live, a perhaps not entirely consistent way of interpreting the world and asking those religious questions outlined by Mueller (1984). One of the tasks for theological students and for academic theology is to interrogate contemporary culture, using music and film or television, as access points to see how it asks and answers the religious questions.

The cult approach invites students to consider their worship, the communication forms that contribute to worship, and the uses of communication in worship. To better grasp the sense of communication in worship, faculty can ask the students to think about how they worship; or, if they can do this without too much distraction, to take notes on a worship service, paying attention to all the communication aspects. Students could also attend to the ways that entertainment forms take on both ritual qualities and roles in the construction of religious meaning.

Creed

“Creed” refers to the abstract formulation of Christian belief. Historically, the first creeds took shape hundreds of years after the death of Jesus. They served as summaries of belief, abstracted from the collection of stories about Jesus (the Gospels), the canonical letters of the New Testament, and the oral kerygmatic tradition. Most people have some familiarity with either the Apostles’ Creed or the Nicene Creed, though fewer will know the history of either one. In a more general sense, however, “creed” refers to any abstract statement of faith. In this sense, any work of theology is a creed, since theology itself aims for an abstract discussion of Christian belief. With this perspective, students, equipped with insights from media ecology, can begin to consider some of the ways in which communication technology plays a role in theology by exploring some key theological concepts that evolved because of an impetus from communication. “Creed,” then, interacts with communication in two ways: first, as a specific content or approach to theology and, second, as the result of the technology of writing.

As Christianity grew and spread throughout the Mediterranean world and encountered the philosophical systems of Greece and Rome, Christians began to ask how they could explain the experience of Jesus. In doing so, they turned from the concrete stories of Jesus to more abstract formulations. The Nicene Creed, for example, speaks of Jesus as “God from God, light from light, true God from true God,” as “begotten not made,” where the Gospels tell the story of birth of Jesus. In Luke’s Gospel, the angel tells Mary that she will conceive by the Holy Spirit and her child will be called Son of God. The creed’s concepts are more abstract. This continues through the history of theology, up to the present day. The media ecology approach calls attention to the ways in which such changes in formulation of Christian belief go together with changes in communication style—in this instance, from oral narratives to written statements.

We also see the development of creed in communication forms such as doctrines (brief statements of belief), catechisms (question and answer books of belief), essays, and books. In many ways, creeds in this sense are works of literacy, whereas collections are works of oral cultures. Creed-type statements depend on writing—on both the abstract kind of thinking facilitated by writing and the ability to organize things and set things down as references that writing provides. Ong (1969, 1982) makes this argument most clearly, identifying the kinds of complex theological statements that depend on writing and, more generally, how “writing restructures consciousness.” In his view, writing as a communication technology enables more detailed recall of information, shifting from forms geared to memorization to external storage in manuscripts and books. Writing allows for collaborative work at great distances in both space and time, since written records can remain unchanged for centuries. Writing fosters more critical distance from ideas, since their creators can set them aside and return to them without the sense of ego-involvement occasioned by the spoken word. Writing, however, lacks immediate context and requires a whole new discipline of interpretation as happens with the rise of hermeneutics, especially in theology.

In addition to communication forms like writing influencing theology, we also see, in the period up to the Enlightenment, that a number of theological concepts emerge in Christian thought that have relevance to communication. While most of these concepts did not consciously develop with reference to communication, many of them apply to it. For example, John’s Gospel starts, “In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God and the Word was God.” The Greek idea of the logos (word or wisdom) fit well with the thinking of the Jewish schools in Alexandria, Egypt and found a place in parts of the Old Testament. The Christians used it to describe the pre-existence of the Divine, incarnated in Jesus. But the term also has a communication dimension; some theologians will use it as a way to understand how God might communicate with humanity. Such thinking will affect what Christians call “revelation” and the human activity of communication.

The approach characterized by “creed” also leads to an examination of how knowledge developed from communication study has influenced theology. In this consideration, we need to bear in mind that communication study has not led to any breakthrough in theology; rather, communication studies have called attention to how certain theological understandings developed historically. We have already seen some of this with the examination of how oral cultures work. Since the Bible emerged from an oral culture, it is not surprising that a great deal of its structure and thought patterns reflect that oral heritage. But the same thing applies to the impact of writing on later theology. The technology of communication makes a difference in how Christians handle the collection (initial narratives, letters, and so on) and creed (abstract statements of belief).

This view builds on media ecology. As we have already noted, media ecology invites us to think of communication, communication technologies, and communication products as the environment in which we live. Since humans adapt to their environments, it should not surprise us that communication technologies and products deeply influence human societies, including how we humans think–whether about God, science, or anything else. The art that we considered in Section 2 affects not only what people think about but also the very way that we think. For example, if the aesthetic conventions always picture heaven as up or above us, then we will treat direction as an important intellectual or psychological aspect of our thinking about God. The same kind of argument might be proposed about how film or television accustoms us to a certain way of seeing; we will bring that way of seeing to our experience of God (Martin, 1991).

Some have made similar arguments about every communication form. For example, people talk about the “language” of film or television. In this analogy, the images we see follow a kind of “grammatical rule” that specifies how directors can combine images to create further meanings. Just has we have to learn the rules of grammar and logic in order to understand written texts, so we have to learn the rules of this visual language. Such grammars also apply to theology. People can only express thoughts in writing, in art, in music, in whatever communication form, by following the “grammar” of that form (McLuhan, H. M., 1964: 13). Whether or not the analogy works, it does call attention to the fact that communication products are made; they do not occur naturally around us. And as with any product, people must learn to use them. Any theology making use of communication forms, then, finds itself constrained by the form.

Media ecology calls attention to another area where communication technology shifts the theological ground. More and more communication technology places us in a virtual world. We are in two places at once. The anthropologist Edmund Carpenter remarks, about the telephone and the television.

Electricity has made angels of us all—not angels in the Sunday school sense of being good or having wings, but spirit freed from flesh, capable of instant transportation anywhere.

The moment we pick up a phone, we’re nowhere in space, everywhere in spirit. Nixon on TV is everywhere at once. That is St. Augustine’s definition of God: a Being whose center is everywhere, whose borders are nowhere. (Carpenter, E., 1972: Ch. 1 )

Here communication technology challenges traditional theological understandings by re-envisioning human life.

More traditional theology—the creed based on abstract thinking—can also draw on insights from communication. Theologians constantly seek greater understanding of the Christian collection and cult. As we have already noted, the more precise answers to theological questions fall under the general heading of “creed.” This is the more abstract way of understanding the collection of source materials, narratives, stories, and teachings that tell us about Jesus.

Occasionally (and all too rarely) some professional theologians will turn to communication in attempts to solve or at least shed light on long-standing problems in theology. Many of the concerns of theology are, after all, communication concerns: How can/does God communicate with humans? How do the various symbolic actions of worship, for example, work? How are we to understand sin—the breaking off of communication, of a relationship with God? Is human language even adequate to talk about God?

If we recall some of the topics that communication study addresses (language, interpersonal relationships/communication, the influence of the media, and the creation of messages in various forms: text, image, song, film, and so on), we find that communication study teaches a great deal about each of these areas; each of them, too, has a place in how we understand and talk about God. If the Gospel of John refers to the Second Person of the Trinity (incarnate in Jesus) as “the Word,” how are we to understand this? Is the Word like a word of language? Does human language itself tell us anything about God? About religious practices?

Appleyard (1971) demonstrates that the study of how language works can help in theology, particularly when it comes to the ritual actions that Christians call “sacraments.” A sacrament, as students will learn in theological terms, “accomplishes what it signifies.” Another definition is that a sacrament is an outward sign of God’s action. So, for example, the ritual of baptism accomplishes a spiritual rebirth. Or the ritual of the Eucharist accomplishes the transformation of the bread and wine offered in the Mass into the Body and Blood of Jesus. One of the long-standing debates in medieval theology had to do with how a sacrament actually worked (making the debate an almost scientific inquiry). But theologians will also use the term generically, as in “the sacramental principle.” Appleyard connects this investigation into sacrament with the linguistic philosophy known as speech acts in order to show how this aspect of communication illuminates a theological debate.

He shows how communication study of language in the last 50 years has offered some insights into symbols and signs. Austin (1975) and Searle (1969) explore language as having more than meaning and encouraging us to realize that we are not really understanding language if we only think of it as a container for meaning. Humans do a lot more with language than mean things. (And, though they don’t remark on this, the idea that languages merely mean seems to come with literacy, when people get used to seeing words on a page rather than hearing them.) Language also accomplishes things, makes things happen, as when two people make a bet. They are not describing a situation, but actually obligating themselves to do a certain thing, contingent upon what happens in the future. Appleyard applies this theoretical understanding to sacraments, arguing that what theologians refer to as the efficaciousness of a sacrament manifests a similar structure to the force of language.

Another key theological question arises in regards to revelation. Can God communicate with humans? This is the basic question of revelation. Theologians and Churches hold that the Bible is how God reveals things to us. How can this be possible if God is completely different from human beings? What exactly does it mean when a Church says that God has revealed something?

Rather than beginning with words, theology could begin with relationships and communication study has a lot to say about relationships. Watzlawick, Beavin, and Jackson (1967) first proposed that any communication has both a content (words, for example) and a relational component. That is, whenever we say anything to another person, we simultaneously offer some content and make a claim about our relationship to that person. We do these things both verbally and nonverbally. If theology deals with our relationship with God, then we could probably conclude that all this communication study about relationships may also be able to shed light on that human-divine relationship. Though he does not cite Watzlawick, Beavin, and Jackson, van Beeck (1991) applies this kind of thinking to the classic theological problem of revelation. He concludes that beginning with relationship and the human experience of relationship best leads to a sustainable theological conclusion that avoids the pitfalls of reducing God’s self-communication to an impossible extrinsic event.

This kind of analysis could continue with any number of theological concepts. Sin, for example, refers to breaking the relationship with God, either directly or through breaking a relationship with others. (Recall the two great commands within Christianity: Love God wholly and completely and love your neighbor as yourself.) Sin, in some ways, could be described as breaking off the communication between God and ourselves or among people (Soukup, 2006). Would such a communication description add anything to what theology says about sin? It might.

Students of theology can benefit from this communication-centric approach to the more abstract topics in theology since it provides an often contemporary context for their studies of historical theological debates. It also offers a non-theological context (in communication technologies, for example) for the movements within theology.

Community

The fourth strand of theology to examine from a communication base is community. If collection is the basic set of documents that inform Christianity; cult, the (communication) practices of Christian worship; and creed, the abstract reflections and development of the collection and cult; then community is the communication among Christians, the communication that creates a body of believers. Theologically, all this can be summarized in St. Paul’s comment in the Letter to the Romans that “faith comes by hearing” and, more pointedly, by Jesus’s command in the Gospel of John, “Love one another.” Both of these lead to the community of Christians.

Without a lot of reflection, most of us would agree that any kind of community is not possible without communication. So, in some ways, this is the easiest part of theology for us to apply to communication or to which we might apply communication. The early Christians used any number of images to describe the possibilities of community. The first involved the Holy Spirit. In the Acts of the Apostles, Luke narrates how the Holy Spirit came upon the apostles and how this allowed everyone in the crowd to hear and understand their preaching in their own languages. The two key aspects of Christian community are joined; the preaching and the creation of a community from a group that had been dispersed. (Many Christian preachers interpret Luke’s narration of this event as a kind of balance to the account in the Book of Genesis in which God mixes up the human languages, thus creating many nations from one original people. Here, the process is reversed and there is one Christian community created from the many human languages.) Other early Christian sources use the images of the body (St. Paul) or of a city (Revelation of St. John). In any event, Christians are to be a community that transcends national or linguistic boundaries—a community in which communication smoothly functions. The Acts of the Apostles also narrates how the community came to define various roles: preaching (adding members), caring for the needs (food, shelter, health, etc.) of the members, and dealing with death.

Communication study devotes a lot of energy to diagnosing and solving communication problems in communities, be those families, businesses, or churches. What kind of communication is most effective? How can we improve our listening to one another? How do we best accomplish our goals?

Other communication studies, particularly those drawn from sociology, call attention to some interesting (or even peculiar) aspect of human communities. While we might initially think of a community as a small group, as a group of people who interact face-to-face, we realize that we can accurately discuss much larger groups as communities—even groups who will never meet. In a work that gets applied to the “virtual communities” of computer-based communication, the political scientist Benedict Anderson (1991) proposes something that he called “imagined communities.” An imagined community exists because people share a common identity based on common beliefs, practices, and documents. For him, the key example is the United States. Citizens cannot know the 300 million people of the country, but all accept one another as being “Americans,” based on some key documents like the Constitution. Brown and Duguid (1995) comment,

Anderson calls the resulting community an “imagined” one. This is no slight. An imagined community is quite distinct from an imaginary community. It is one, Anderson notes, whose members “will never know most of their fellow members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion.” Where an imaginary community does not exist, an imagined one exists on too large a scale to be known in any other way. And the central way they can be imagined is through the documents they share. (Brown, J. S. & Duguid, P., 1995: Section 4)

This sounds a lot like a Church, too: we know small segments of the Christian community, but cannot know everyone. We live in a short historical period of the Christian community, whose life spans millennia. And yet we accept a Christian identity and find the Christian community essential to any kind of religious practice.

Stock (1983) makes a similar argument and applies it to Christian groups in the Middle Ages, when he discusses “textual communities.” These are groups who base their identity on a given text—the Bible, the Rule of St. Benedict, etc. Even if only a few of the group can read, the non-readers receive their identity from hearing the key texts read to them. They base their lives on interaction with key texts—the collection and the creed—and these actions form into the cult–ritual practices and code modes of behavior. While Stock was more interested in how literacy enters into and changes an oral group, his argument helps us to understand how communities work.

Since communication plays a central role in any group—its formation, the recruitment of new members, its maintenance, its accomplishment of goals, etc.—groups will use whatever kinds of communication available to them. Face-to-face groups experience the limitation of the voice and of time; textual groups can span continents and centuries. Mass media groups grow even larger and exist in a simultaneity like that of oral ones.

In a theological work on the nature of the Church, Dulles (1989) tries to correlate various kinds of communication to different theological understandings of what the Church is. His “models of the Church” (Dulles, A., 1974) describe various structures of Christian community and then asks how each functions. The Church is such a complex organization that each of these models accurately describes it, yet no one model is sufficient to make sense of the Church as a whole. He proposes five models. First, if we consider the Church as an institution, we focus attention on its structures, government, and official communication, which often takes the forms of printed documents or top-down statements from the Pope to the members. The mass media fits this model, since with it an individual leader can address large numbers of people. Second, Dulles writes that we can also see the Church as a herald, as an entity announcing the Gospel. Here the communication depends on all the members proclaiming or telling people about Jesus. Third, we can also describe the Church as a sacrament, as a sign of the presence of Christ. The communication of this model occurs primarily in cult or worship and the community is formed in those moments of worship. Fourth, Dulles uses the language of communion or community to describe the Church. Here he places emphasis on the interpersonal communication among the Church members. Finally, the Church is a servant. This model highlights the action of the Church in service to others and the communication largely takes the form of actions and community services. In these works Dulles clearly demonstrates how communication study illuminates the theological analysis of the church community.

In the consideration of community, then, communication studies can offer the analysis of various kinds of communication (mass media, interpersonal, group, etc.) while theology will inquires as to what makes a community religious. The larger Christian community will be an imagined one, held together by fidelity to the Scriptures and the use of common narratives (Gospels), common worship (cult), and common beliefs (creed).

Such an approach opens the way for more detailed considerations of the Church. Starting with communication begins with the human organization and takes a kind of sacramental approach, showing the nature upon which grace builds. The approach also clarifies contemporary debates, such as the role of dialogue within the Church (Pottmeyer, H., 2001).

Code

“Code,” the final theological area to consider, deals with how people should behave, what code of conduct they should follow. Religions always provide some instruction and guidance for human behavior; these differ from ethics in that they seek to follow an ideal of conduct drawn not only from human reason, but also from the teachings of the religion. Christianity proposes what has been termed an ethics of love, insofar as it follows the teaching of Jesus that we love God wholeheartedly and love our neighbor as ourselves. This one command appears multiple times in the New Testament: “Love one another as I have loved you.”

The branch of theology that deals with behavior is called moral theology; as an organized reflection on belief and on our relationship with God, it seeks to move from the general command to love one another to specific guidance regarding how we do that in various situations. Obviously a complete moral theology or ethical system would govern all aspects of human behavior. In thinking about theology and communication, we can limit the exploration.

On the one hand, we should look at what moral theology has to say about communication ethics. What does Christianity have to say about how we should communicate? About how individuals and society at large should address questions about communication? These include not only interpersonal things like lying but also other forms of deception, at the corporate, institutional, and state levels, too. Such an ethics considers the effects of mass communication such as violence, pornography, persuasion, etc. It also would consider structural issues like people’s access to communication. In fact, according to the United Nations, Communio et Progressio (Pontifical Council, 1971) was the first place to recognize an individual’s “right to communicate.” Catholic moral theology develops all of these topics in a method that combines Biblical sources and principles with reasoned deduction. This moral theology tradition is also influenced by natural law philosophy, a method that tries to understand how humans should act based on the inherent purpose of the action. The Pontifical Council for Social Communication demonstrates how these methods work in its 2000 document, Ethics in Communication. Such a document provides students of theology a starting point from which to consider moral theology as applied to an important and powerful part of contemporary living.

On the other hand, this consideration of codes of conduct might also ask whether communication study can inform moral theology. This argument may be more difficult to make, but if communication itself is an end or goal of human living, then (following a kind of natural law approach), one could deduce some guidelines from free and open communication. If people have a right to communicate, then this right will lead to a number of practical consequences, especially in institutional or government involvement with individuals (free speech, access to information about the institution or government, public opinion, and so on). A number of communication scholars, led by Hamelink (1996), have developed this line of thinking. Rossi and Soukup (1994) publish essays by other scholars who explore how contemporary media informs the moral imagination, leading people to particular kinds of ethical decisions.

Conclusion

The media ecology approach allows a broader scope of inquiry into the relationship of theology and communication. We see this in each of the five general categories of theological inquiry—collection, cult, creed, community, and code—where the ecological perspective combines history investigation with contemporary engagement. The approach also helps students to see communication as a condition under which theological reflection takes place as well as an invitation to engage in theological expression using the means typical of their own cultures. As outlined here, the topics could constitute units within courses on historical theology, liturgy, Scripture, moral theology, ecclesiology, and so on. They could also serve as parts of a stand-alone course in theology and communication. However, given all that occurs within a theological education, the topic-within-a-larger course approach may benefit the student more, since the overall focus continues to fall on theology. The communication or media ecology perspective simply gives the students an additional lens through which to see what happens when the Church reflects on its belief.

References

Anderson, B. (1991). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nations. London and New York: Verso.

Appleyard, J. (1971). “How does a sacrament ‘cause by signifying’?” Science et Esprit, 23: 167-200.

Augustine. (1947). De doctrina Christiana. In Writings of Saint Augustine (Vol. 4, pp. 3-235), (Trans. J. J. Gavigan), New York: CIMA Publishing Co., Inc.

Austin, J. L. (1975). How to do things with words, 2nd ed. (J. O. Urmson & M. Sbisà, Eds.), Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Blake, R. A. (2000). Afterimage: The indelible Catholic imagination of six American filmmakers, Chicago: Loyola Press.

Boomershine, T. (2001). “Toward a Biblical communication theology.” Catholic International, 12/4: 27-31.

Brown, J. S. & Duguid, P. (1995). “The social life of documents.” Retrieved May 23, 2007 from http://www2.parc.com/ops/members/brown/papers/sociallife.html.

Carey, J. W. (1989). Communication as culture: Essays on media and society, Boston: Unwin Hyman.

Carpenter, E. (1972). Oh, what a blow that phantom gave me. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. Retrieved May 22, 2007 from http://www.mediatedcultures.net/phantom/home2.html.

Clark, L. S. (2003). From angels to aliens: Teenagers, the media, and the supernatural. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Dulles, A. (1974). Models of the church. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Dulles, A. (1989). ‘Vatican II and communications’ in R. Latourelle (Ed.), Vatican II: Assessment and perspectives, twenty-five years after (1962-1987), (Vol 3, pp. 528-547), New York: Paulist Press.

Duncan, H. D. (1962). Communication and social order, New York: Bedminster Press.

Dunn, James D. G. (2001). “Jesus in Oral Memory: The initial stages of the Jesus tradition” in D. Donnelly (Ed.), Jesus: A Colloquium in the Holy Land (pp. 84-145), New York: Continuum.

Ferree, B. (1898). “Bibles in stone.” New England Magazine, 24/3:162-177. Retrieved May 24, 2007 from http://cdl.library.cornell.edu/cgi-bin/moa/moa-cgi?notisid=AFJ3026-0024-24.

Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Introduction of the theory of structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Goethals, G. (1981). The TV ritual: Worship at the video altar. Boston: Beacon Press.

Goethals, G. (1990). The Electronic golden calf: Images, religion, and the making of meaning. Cambridge, MA: Cowley.

Goethals, G. (1999). “The imaged word: Aesthetics, fidelity, and new media translation.” In P. A. Soukup & R. Hodgson (Eds.), Fidelity and Translation: Communicating the Bible in new media (pp. 133-172). Franklin, WI: Sheed & Ward.

Hamelink, C. (1996). “Globalization and human dignity: The case of the information superhighway.” Media Development, 43/1: 18-21.

Harris, M. (1989). Fashion me a people: Curriculum in the church. Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox Press.

John Paul II. (1990). Redemptoris Missio, Retrieved May 23, 2007 from http://www.vatican.va/edocs/ENG0219/_INDEX.HTM

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1966). The savage mind (Pensée sauvage). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lindvall, T. (2004). “Religion and film: Part I: History and criticism.” Communication Research Trends, 23/4: 1-44.

Lindvall, T. (2005). “Religion and film: Part II: Theology and pedagogy.” Communication Research Trends, 24/1:1-40.

Lindvall, T. (2007). Sanctuary cinema: Origins of the Christian film industry. New York: New York University Press.

Lytle, J. A. (2005). Fashioning-a-people in an interactive age: The potential of computer-mediated communications for faith formation. Dissertation, Boston College. Dissertation Abstracts International, 66, no. 03A, 943.

Martin, T. M. (1991). Images and the imageless: A study in religious consciousness and film. 2nd ed. Lewisburg: Lewisburg University Press.

May, J. R. (Ed.). (1997). New image of religious film. Kansas City, MO: Sheed & Ward.

Mead, G. H. (1962). Mind, self, and society: From the standpoint of a social behaviorist (C. W. Morris, Ed.). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding media: The extensions of man. New York: McGraw Hill.

Mueller, J. J. (1984). What are they saying about theological method? New York: Paulist Press.

Ong, W. J. (1969). “Communications media and the state of theology.” Cross Currents, 19: 462-480.

Ong, W. J. (1982). Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. London and New York: Methuen.

Pontifical Council on Social Communication. (1971). Communio et Progressio. Retrieved May 23, 2007 from http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/pontifical_councils/pccs/documents/rc_pc_pccs_doc_23051971_communio_en.html.

Pontifical Council for Social Communication. (2000). Ethics in communication. Retrieved May 23, 2007 from http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/pontifical_councils/pccs/documents/rc_pc_pccs_doc_20000530_ethics-communications_en.html.

Postman, N. (1970). “The reformed English curriculum.” In A.C. Eurich (Ed.), High school 1980: The shape of the future in American secondary education (pp.160-168). New York: Pitman.

Postman, N. & Weingartner, C. (1971). The soft revolution: A student handbook for turning schools around. New York: Delacorte.

Pottmeyer, H. (2001, November). “Dialogue as a model for communication in the Church.” Catholic International, 12/4: 40-43.

Rossi, P. & Soukup, Paul A. (Eds.). (1994). Mass media and the moral imagination. Kansas City, MO: Sheed and Ward.

Schrader, P. (1972). Transcendental style in film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Searle, J. R. (1969). Speech acts: An essay in the philosophy of language. London: Cambridge University Press.

Shea, J. (1980). Stories of faith. Chicago: Thomas More Press.

Soukup, P. A. (2002). “Media and religion.” Communication Research Trends, 21/2: 3-30.

Soukup, P. A. (2003). “The structure of communication as a challenge for theology.” Teologia y Vida, 44 /1: 102-122.

Soukup, P. A. (2006). Out of Eden: Seven ways God restores blocked communication. Boston: Pauline Books and Media.

Stock, B. (1983). The implications of literacy: Written language and models of interpretation in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Strate, L. (2004) “A Media Ecology Review.” Communication Research Trends, 23/2: 3-48.

Tilley, T. & Zukowski, A. A. (2001). “Narrative and communication theology in a post-literate culture.” Catholic International, 12/4: 5-11.

Van Beeck, F-J. (1991). “Divine revelation: Intervention or self-communication.” Theological Studies, 52: 199-226.

Watzlawick, P., Beavin, J. H., & Jackson, D. D. (1967). Pragmatics of human communication: A study of interactional patterns, pathologies, and paradoxes. New York: Norton.